Lupine Publishers - Dentistry and Oral Health Care

Monday, March 2, 2020

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Post Endodontic Pain Reduction...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Post Endodontic Pain Reduction...: Lupine Publishers | Journal of Otolaryngology Research Impact Factor Abstract Objective: The pur...

Sunday, March 1, 2020

Lupine Publishers | Oral Hygiene Habits and Dental Treatment Needs of Children with Dental Fluorosis and Those Without Dental Fluorosis Aged 12-15 Years In in a High Fluoride Area in North Kajiado Kenya

Lupine Publishers | Journal of Oral Healthcare

Abstract

Background: The dental disease identified as dental caries,

periodontal, gingival lesions and dental fluorosis when diagnosed

early and the treatment needs assessment with patients’ perception

ensures the proper use of the physical facilitates, It also

enhances planning for rational health resource allocation, utilization

and personnel distribution so as to tackle the health problems

in a holistic way.

Objective: The objective of the study was to determine the dental treatment needs among children aged 13-17 years affected by

dental fluorosis and those not affected by dental fluorosis in Kajiado North District of Kenya

Materials and Methods: Study design this was a cross sectional

comparative study of the dental treatment needs among two

age matched population groups in primary school children. Sampling and

Sample size. Stratified random sampling was used to

select four primary schools out of the primary schools in North Kajiado.

All children in the school with a full permanent dentin and

whose parents had signed the consent form were recruited into the study.

The study involved 248 children, 98(40%) males and

150(60%) females aged between 13 -17 years (mean age = 14.75±1.45)

selected by simple random sampling from 9 schools in

Kajiado North District which was purposively selected. They were all

clinically examined under natural light for plaque and gingival

scores using the Silness and Loe 1, Loe and Silness, dental caries was

recrded using the decayed Missing Filedl teeth (DMFT), while

gingivitis, periodontal disease and fluorosis using indices:- Silness

and Loe 1, Loe and Silness, DMFT,CPITN and TFI.

Results: The treatment needs for gingivitis were similar,

majority 218 (88%) children with fluorosis and 213 (86%) without

required oral hygiene instructions and prophylaxis. There were 3(1.2%)

children who had periodontitis in the group with dental

fluorosis and required scaling and root planning. There were 50%

children with caries in the fluorosis group who required one

surface and 24.2% for two surface amalgam/composite restorations and for

those without fluorosis, 76% required one surface and

15.2% two surface amalgam/composite restorations. There were 321(60.8%)

teeth surfaces which required bleaching and microabrasion

or composite masking and another 207(39.2%) for direct composite /

porcelain veneers or crowns.

Conclusion: Children with dental fluorosis were burdened more by dental disease and had more treatment needs (dental caries,

fluorosis, periodontal disease and gingivitis) when compared to those without dental fluorosis.

Introduction

Dental conditions like fluorosis, caries, gingival and periodontal

diseases require varied treatment approaches to manage them

depending on the severity hence the need to establish the levels of

disease burden and treatment needs for proper planning of dental

services. Well assessed dental treatment needs go a long way in

the estimation of resources, rational fund allocation and efficient

utilization of dental materials. Dental treatment needs should be

assessed objectively and subjectively based not only on normative

assessment but also on perceived needs and impact so as to obtain

the best outcomes. The incorporation of both the clinician’s objective

assessment and the client’s felt needs is essential in ensuring that

they participate in the general management of their condition. In

common practice today Bradshaw (1978) in a study on the problems

and progress in medical care said that the treatment needs of most

dental conditions are based on the clinician’s judgement using

the recommended dental indices1. The age between 13-17 years

forms the transition period between childhood and adulthood.

The growth changes seen during this stage of life warrants a clear

understanding of the health needs in general and support for

optimal psychosocial and emotional development. Welbury pointed

out that children affected by fluorosis suffer from low self - esteem,

social stigma and poor performance in school.

Facial image is an important aspect with regard to an individual’s

presentation and self-esteem in communication. This is greatly

affected by the presence of dental fluorosis among other things

like mal-aligned teeth, missing anterior teeth or even congenital

malformations of the oral cavity. Globally there is often a permanent

stigma associated with dental fluorosis among children or adults. A

study conducted in Brazil by Rodriques showed esthetic changes

in the permanent dentition are the greatest concern in dental

fluorosis. Studies by Welbury and Glasser have observed that if left

untreated, dental fluorosis causes embarrassment, psychosocial

distress, difficulties in societal adjustment, damage to self-esteem

and poor performance for the school-going children. Another study

in Kenya by Mwaniki showed that between 60.4% and 84.3% of the

respondents viewed dental fluorosis as a problem because of its

unfavourable effects on an individual’s personality. It is important

to note that dental fluorosis leads to shyness in expression thereby

masking the true personality of an individual. It is further evidenced

by a South African study by Mothusi that showed the trauma

suffered by young people with dental fluorosis to be depressing

such that they requested to have the teeth extracted and replaced

with dentures.

Generally, the quality of life is greatly affected by oral diseases,

dental fluorosis not being an exception, with a significant impact

on the 13-17- year- olds due to their delicate stage of growth

and development. Children experience appreciable impacts on

oral health related quality of life with the greatest burden being

associated with dental caries and to a lesser extent, fluorosis

according to a study in Uganda by Robinson. The aspects considered

when determining the quality of life with regard to oral diseases

using the oral impact of daily performance (OIDP index) include

eating, speaking and pronouncing clearly, cleaning teeth, sleeping

and relaxing, smiling without embarrassment, maintaining

emotional state and enjoying contact with others. A study in

Tanzania by Roman on the impact and treatment needs of dental

fluorosis where a total of 269 students with dental fluorosis aged

15-18 years (mean age 17.3) were involved, showed that a majority

(65.4)% had severe dental fluorosis (TFI 6-9) while 29.4% had TFI

4-5 and 5.2% had TFI 1-3. Most of the students in this study (92.6%)

perceived at least one (OIDP) with the most affected being smiling

at 88.1%, emotional stability 81.4%, and having contact with others

75.5%. Studies by Locker and Leake indicated that the oral health

status of at risk children and adolescents appeared to have been

poor resulting in the need for several treatments including urgent,

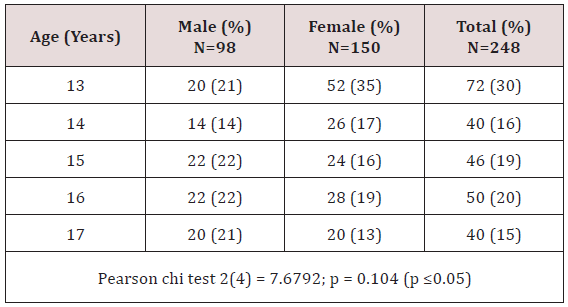

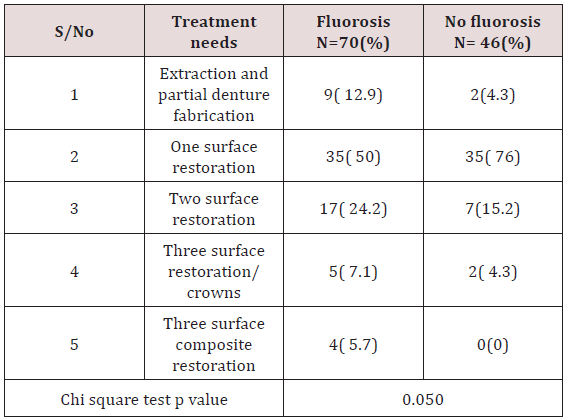

restorative, periodontal and preventive care Table 1.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The study population comprised of 13 -17- years who were

born and brought up in Kajiado North District in the first 7 years

of life. The target population involved 34,122 children aged 13-

17 years according to the Kenyan population and housing census

2009 for Kajiado North District. The public primary and secondary

school enrolment was approximately 19,065 for the ages 13-17

years in the year 2011 in the study involved 248 children, 98(40%)

males and 150(60%) females aged between 13 -17 years (mean

age = 14.75 ±1.45) selected by simple random sampling from 9

schools in Kajiado North District which was purposively selected.

They were all clinically examined under natural light for plaque

and gingival scores, dental caries, gingivitis, periodontal disease

and fluorosis using indices:- Silness and Loe 1963, Loe and Silness

1964, DMFT,CPITN and TFI. Information on biodata, consumption

of sugary snacks, brushing was collected using an interviewer

administered questionnaire. Water samples were collected for

testing for fluoride levels at the government chemist laboratories.

Data analysis

The clinical examination forms were pre-coded. The quality of

data was ensured during the entire study process especially at the

data collection point to include completeness of questionnaires,

and validity of responses. Data was de - indentified and stored in

a password protected data base with access being granted to the

statistician. Quality control through data cleaning and validation

was censured by counter checking frequencies in the computer and any

missing data was re - entered. The findings from the study were

organized in the form of frequency tables and figures. Computations

to calculate disease burden (caries experience, prevalence of

gingivitis and periodontitis, treatment needs and the cost of

treatment) were done. The independent variable for this analysis

was presence/absence of fluorosis while the dependent variables

were age, gender, gingivitis, periodontitis, caries experience and

cost of treatment. The confounding factors were snacking and oral

hygiene practices. For categorical variables association between

dependent variables and fluorosis was tested using a Pearson

Chi-square test while a student t-test was used for continuous

variables and the conventional P value of cut-off of < 0.05 was used

to establish a significant association. To calculate the total DMFT,

the total number of teeth per child with caries, filled due to caries,

missing due to caries was summed up. For the mean gingival and

plaque scores, the total score per child was calculated by summing

the individual tooth scores, divided by 6 and the total for the index

teeth added and divided by 6. To determine the agreement rates

between assessors, a Cohen kappa score (agreement rate) was

calculated for each assessment (tooth and surface) for all children

assessed. A median agreement rate was then computed from all

individual scores calculated. Data collected was analyzed using

statistical package for social sciences (SPSS version 17.0) Table 2.

Results

Socio demographic characteristics

This study involved 248 children aged between 13-17 years

with a mean age of 14.75 years (±1.45 SD) who were all matched

for age and gender. The ratio of children with dental fluorosis and

those without was 1:1 and the male to female ratio was 2:3 and was

not statistically significant [p= 0.104 (p ≤0.05)] as shown in Table

1. There were 241 (97%) participants born and raised in Kajiado

North while 7(3%) moved to the district before 7 years of age.

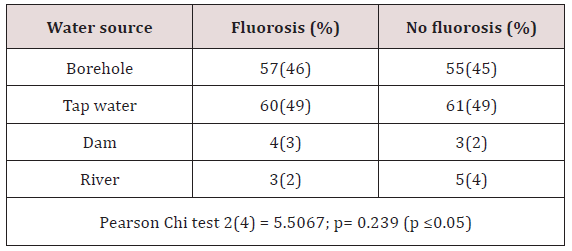

Source of water and analysis

There was a similar pattern on the water sources which was

not statistically significant [p=0.239 (p≤0.05)] for children with

fluorosis and those without fluorosis. Most of the study participants

consumed borehole water and most of tap water was also from

boreholes. Dams and river sources were for a minority group as

shown in Table 3.

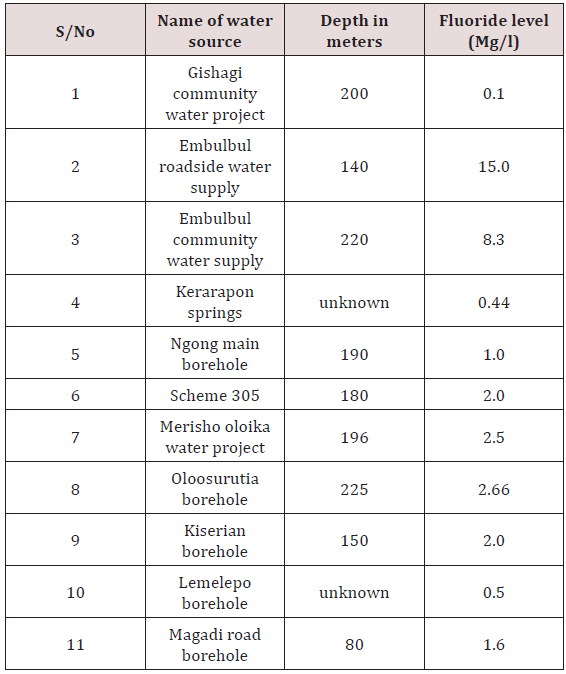

Gishagi borehole which is in a raised ground recorded low

fluoride levels of 0.1 ppm as well as Kerarapon springs 0.44 and

Lemelepo borehole 0.5, Ngong main borehole had the recommended

levels by WHO of 1ppm. Embulbul roadside and Embulbul

community water supplies had very high levels of fluoride at 8.3

and 15ppm (Table 4).

Tooth brushing habits

Majority of the children 122(98%) from each group brushed

their teeth, the frequency of brushing was similar where by

113(93%) with fluorosis and 105(88%) without used a toothbrush

while a chewing stick was used by a few (Table 5). The type of tooth

brushing aid used was not statistically significant p=0.120(p≤ 0.05).

Majority brushed once a day either in the morning after breakfast

61(50%) and 59(48%) or in the evening after meals 49(40%) and

51(42% for the children with fluorosis and those without fluorosis

respectively. Only a small percentage brushed their teeth twice a

day. There was no statistical significant difference on the timing of

brushing between the groups [p=0.180(p≤ 0.05].

Relationship between brushing habits and plaque scores

Generally, children who brushed once after breakfast in both

groups had PSs which were statistically significant p=0.003(p≤0.05)

and the children with fluorosis had the lowest PSs of 0.85(0.5).

The other brushing timings were not statistically significant

p=1.02(p≤0.05) for at night and p= 0.664(p≤0.05) for twice a day

as depicted in.

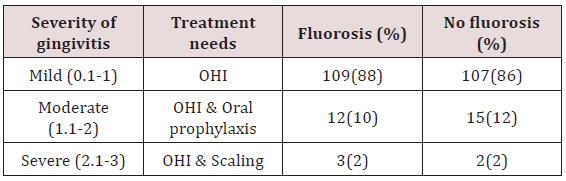

Gingivitis

Both groups had a similar pattern of treatment needs. There

were 109(88%) for OHI, 12(10%) OHI and oral prophylaxis, 3(2%)

OHI and scaling for children with fluorosis. Those without fluorosis,

107(86%) OHI, 15(12%) OHI and oral prophylaxis, 2(2%) OHI and

scaling.

Periodontitis

Of the 3(2.4%) children with fluorosis who had periodontitis

they all required scaling and root planing.

Dental caries

In both groups, dental restorations in form of one surface fillings

were mostly indicated as 35(50%)/ 35(76%) for the children

with fluorosis/those without. Two surface restorations 5(7.1%)

for fluorosis and 7(15%) those without fluorosis. Extraction and

partial dentures 9(12%) for fluorosis and 2(4.3%) those without

fluorosis. Three surface composite restorations among children

with fluorosis were 4(5.7%).

Caries experience in relation to consumption of sugary snacks

In the group with fluorosis the children who consumed sugary

snacks twice had a higher DMFT of 0.71(1.4) while children

without dental fluorosis and consumed four times scored highest

DMFT of 0.83(0.9). On the weekly snack consumption, those who

sacked once had no caries in both groups p=0;000(p≤0.05) which

was statistically significant while the highest DMFT was recorded

in those who snacked twice/four times for the fluorosis group at

0.64/0.6 while in the group without fluorosis the scores ranged

between 0.17-0.25 despite different weekly snacking times.

None of the children who brushed twice had dental caries

experience in the fluorosis group for once a day (after breakfast or

at night) had a DMFT of 0.5(1)/ 0.73(1.6). For the group without

fluorosis, there was some caries experience despite the timings for

brushing. Generally there was no statistical significant difference on

the brushing timing for both groups. The children who brushed after

breakfast had a p=0.850(p≤0.05), at night only p=0.073(p≤0.05)

and twice a day p=0.217(p≤0.05) therefore, brushing did not have

any influence on the caries experience.

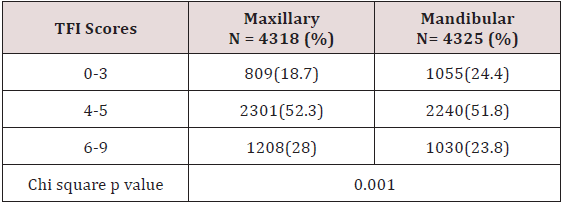

Cumulative TFI frequencies

In both jaws TFI 4-5 was the most frequent at 2301(52.3%)

on the labial and lingual surfaces of the anterior teeth in both the

maxilla and of the mandibular anterior teeth 2240(51.8%). There

were 321(60.8%) surfaces which required bleaching and/or

micro abrasion or composite masking while 207(39.2%) surfaces

required porcelain veneers or crowns Table 6.

Discussion

The current study did not find much difference in the treatment

needs for gingivitis between the two groups as majority 88%

with fluorosis and 86% without fluorosis required oral hygiene

instructions and oral prophylaxis and in periodontitis the 1.2%

affected required scaling and root planing. Most of the subjects with

dental caries required some form of restorations either one, two or

three surface amalgam/ composite restorations. A smaller number

required extractions and partial dentures. Since radiographs

were not taken for this study, it was difficult to ascertain the teeth

which were indicated for pulp therapy. Studies done in Trinidad

and Tobago by Naidu and Uganda by Nalweyiso clearly indicated

that the treatment burden of dental caries is mainly centered on

fillings, fissure sealants, pulp therapy and extractions. This study

considered treatment needs for dental fluorosis in terms of labial

surfaces from canine to canine in the maxillary teeth only. It was

established that 48% of the teeth surfaces required bleaching /

micro abrasion, composite masking and 52% for direct/indirect

composite veneers/crowns. In Kenya Mwaniki found that 60.4

- 84.3% of the respondents viewed dental fluorosis as a problem

although the study design was different from the current study.

Conclusion

Children with dental fluorosis were burdened more by dental

disease and had more treatment needs (dental caries, fluorosis,

periodontal disease and gingivitis) when compared to those

without dental fluorosis.

Read more Lupine

Publishers Blogger Articles please click on: https://lupinepublishers.blogspot.com/

Read more Lupine Dentistry Journal Blogger Articles please click on: https://lupine-dentistry-oral-health-care.blogspot.com/

Follow on Twitter : https://twitter.com/lupine_online

Friday, February 28, 2020

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | The Influence of Yoga on Traum...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | The Influence of Yoga on Traum...: Lupine Publishers | Open access Journal of Complimentary & Alternative Medicine Abstract Sustaining a Traumatic Br...

Thursday, February 27, 2020

Lupine Publishers | Bioactivity, Biocompatibility and Biomimetic Properties for Dental Materials: Clarifying the Confusion?

Lupine Publishers | Journal of Oral Healthcare

Abstract

Often in the profession of dentistry, a new or novel instrument, material,

technique, and/or “system” is introduced which can incur a “state-of-the-art”

status without necessarily being subjected to the rigors of clinical testing or

longitudinal patient-based studies prior to receiving the stamp of approval or

the moniker of “standard of care”. Recently, provocative terminology

surrounding the field of dental materials has been publicized through the

literature, promoting exciting claims and possible long-term advancements for

patient care. In this “new era” of evidence-based restorative dentistry;

conservative interdiction, i.e. “informed” removal of diseased tissue with

concurrent substitution considering form and function, esthetics, and the

interaction of the physical and mechanical properties of the replacement

materials with living, dynamic structures found in the human tooth, has been of

paramount importance.

Abbrevations: ACP: Amorphous Calcium Phosphates, MTA: Mineral

Trioxide Aggregate, PVPA: Poly Vinyl Phosponic Acid, PAA: Polyacrylic Acids

Introduction

The progression or evolution of dentistry has occurred, to a great degree,

in concert, with the development of material technology [1]. During the last

two decades, the categorization of dental materials, specifically, adhesive

systems and composite resins have included the term “nanotechnology” into the

lexicon of scientific literature [2]. Nanotechnology involves the science and

engineering of functional molecules at the nanoscale (onebillionth of a meter)

level [2]. As applied to dentistry, this innovative approach promotes the

incorporation or interaction of nanostructured materials together with the

complex arrangement of organic/inorganic molecular-level constituents

comprising living tooth structure, allowing for a myriad of possible preventive

and therapeutic applications [2]. Owing to this progression of material

development, the assignments of additional revolutionary dimensions have

included the origination of the concepts of biocompatibility or bioactivity into

dental science.

As a possible expansion of nanotechnology applied to dental materials: the

terms biocompatible, bioactive, bioinduction, and biomimetics can be defined

independently; however, have often been characterized synonymously [3].

Biocompatible is simply a term to describe a substance or material that will do

no harm to existing living structures, that is non-mutagenic and noncytotoxic.

The term “bioactivity” was first described in 1969 by Hench, whereby a

“bioactive material is one that elicits a specific biological response at the

interface of the material which results in the formation of a bond between the

tissues and the material” [4]. Furthermore, the definition was refined and

updated to include two categories based upon intent and procedure, originally

pertaining, specifically, to bone tissue:

a) Class A: A material that elicits an intracellular and extracellular

response (osteoproductive);

b) Class B: Materials eliciting an extracellular response only

(osteocontuctive) [5].

Accordingly, a bioactive material can have “the effect on, or eliciting a

response from living tissue, organisms, or cells”, thus contributing to the

formation of a new substance or creation of a living, compatible system [3]. A

bioinductive property is defined as “the capability of a material for inducing

a response in a biologic system”[3]. Biomimetics is the “study of formation,

structure, or function of biologically produced substances and materials and

biological mechanisms and processes for the purpose of synthesizing similar

products by artificial mechanisms that mimic natural substances”[3,6]. So,

although these terms seem to imply different connotations, what can a dental

practitioner conclude, deduce, and/or apply for everyday use? Any substance,

arrived from by any process (bioactive, bioinduction, biomimetic) should

exhibit attributes of being biocompatible. It appears that both a bioactive and

biomimetic substance can include the process of bioinduction and that a

biomimetic substance could possibly be produced through bioactive activities.

Bioactive materials and processes are probably the most applicable for

endodontics and restorative dentistry based upon current uses: luting cements,

pulp capping agents, root repair materials, permanent restorations, hard tissue

remineralization (fluoride, calcium, and phosphate ions) and bone regeneration

properties, and treatment of dentinal hypersensitivity[1,3,7-13]. In order for

these materials to become biocompatibily active or retain characteristics of

bioactivity; bactericidal and bacteriostatic (inhibits bacterial growth and

biofilm formation) properties for the stimulation of reparative dentin

formation and maintenance of pulpal vitality must be achieved and maintained

[3]. Examples include fluorides for remineralization, antibacterial resins and

cements (Reactimer bond™ Shofu Dental Corp., Kyoto, Japan; ABF™ Kuraray,

Kurasiki, Japan), restoratives (Active™ BioACTIVE, PULPDENT Corp., Watertown,

MA, USA) releasing fluorides and containing amorphous calcium phosphates [ACP],

medicaments (mineral trioxide aggregate [MTA] and bioaggregate; Biodentine™,

Septodont, Lancaster, PA, USA; TheraCal™, Bisco Dental Products, Schaumburg,

ILL, USA; and Endosequence root repair [RRM]™, Brasseler USA, Savannah, GA),

and luting cements (Ceramir Crown & Bridge, Doxa Dental Inc., Chicago, ILL,

USA) that induce healing and/or for creation of new tooth

structures[1,3,7,8,10-14]. Biomimetic substances include the usage of

polyvinylphosponic acid (PVPA) polyacrylic acids (PAA) as calcium phosphate

matrix protein analogues for remineralization purposes [7,15].

Conclusion

Although these materials are in their infancy, with long-term efficacy based

on improvements of mechanical and physical properties pending, future materials

will hopefully create circumstances for increased tooth-like attributes due to

properties of adhesion, remineralization, and integration [1,3,7].

Read more Lupine

Publishers Blogger Articles please click on: https://lupinepublishers.blogspot.com/

Read more Lupine Dentistry Journal Blogger Articles please click on: https://lupine-dentistry-oral-health-care.blogspot.com/

Follow on Twitter : https://twitter.com/lupine_online

Tuesday, February 25, 2020

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Hypertrophic Cardiomiopathy in...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Hypertrophic Cardiomiopathy in...: Lupine Publishers | Journal of Cardiology & Clinical Research Abstract Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most co...

Monday, February 24, 2020

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | We Hear With our Brain as the ...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | We Hear With our Brain as the ...: Lupine Publishers | Journal of Otolaryngology Research Impact Factor Abstract There are some stu...

Lupine Publishers | Down’s Syndrome- A Disease Caused By Genetic Alteration

Lupine Publishers | Dentistry Open Access Journal

Abstract

Down’s syndrome is the most common syndrome, medical professional

encounters in day to day practice. It is a genetic disorder

with a typical face profile and few classical intraoral features. Herein

we report case and review on Down’s syndrome with facial

features.

Keywords: Down’s Syndrome; Trisomy; Chromosome; Oral Manifestation

Introduction

Down syndrome is one of the commonest disorders with huge

medical and social cost. DS is associated with number of phenotypes

including congenital heart defects, leukemia, Alzheimer’s disease,

Hirsch sprung disease etc. [1]. Down syndrome is a prevalent

genetic disorder in intellectual disability in India. Its prevalence in

tribal population is not known [2]. Down syndrome is one of the

leading genetic causes of intellectual disability in the world. DS

alone accounts 15-20% of ID population across the world [3,4].

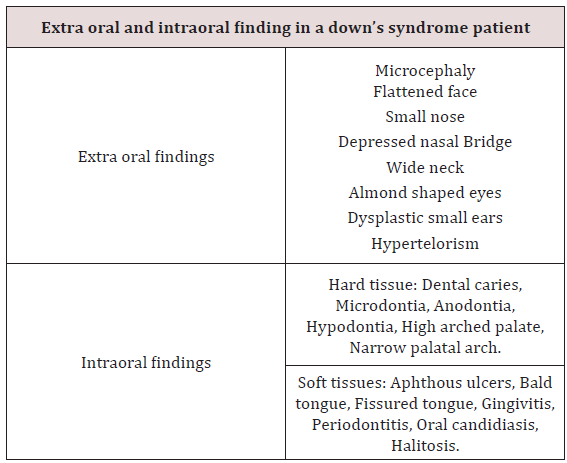

Case Report

An 8 year old male patient came to the department of oral

medicine and radiology for routine dental check-up. Extra oral

examination revealed characteristic facial profile with increased

inter canthal distance (Figure 1). Intraoral examination revealed

Gingiva was soft with deposits on the teeth, High arched palate,

with depressed nasal bridge was seen (Figure 2). Macro glossia

was also seen .Correlating the intraoral and extra oral findings a

Provisional diagnosis of Down’s syndrome/ Trisomy 21 was given.

Patient was referred to the respective departments of pedodontics

for restoration of decayed teeth.]

Discussion

Down syndrome is one of the most leading causes of

intellectual disability and millions of these patients face various

health issues including learning and memory, congenital heart

diseases, Alzheimer’s diseases, leukemia, cancers and Hirsch rung

disease. The incidence of trisomy is influenced by maternal age and

differs in population [5,6]. Facial findings in the patients can be

characterised into extra oral and intraoral features (Table 1) [7].

Parents of children with Down’s syndrome should be aware of these

possible conditions so they can be diagnosed and treated quickly

and appropriately. According to Asim A et al. A Down’s syndrome

child should have regular check-up from various consultants. These

include:

a) Clinical geneticist - Referral to a genetic counselling

program is highly desirable.

b) Developmental paediatrician.

c) Cardiologist - Early cardiologic evaluation is crucial for

diagnosing and treating congenital heart defects, which occur

in as many as 60% of these patients.

d) Paediatric pneumonologist -Recurrent respiratory tract

infections are common in patients with DS.

e) Ophthalmologist.

f) Neurologist/Neurosurgeon - As many as 10% of patients

with DS have epilepsy; therefore, neurologic evaluation may be

needed.

g) Orthopaedic specialist.

h) Child psychiatrist - A child psychiatrist should lead liaison

interventions, family therapies, and psychometric evaluations.

i) Physical and occupational therapist.

j) Speech-language pathologist.

k) Audiologist.

l) Paediatric dentist.

Hackshaw AK et al in their study, proposed a new screening

method in which measurements obtained during 1st and 2nd

trimester are integrated to provide the risk status of having

pregnancy with DS. Moderate to severe intellectual disability occur

as a constant feature, with IQ’s ranging from 20 to 85 [8]. Kennard

in his review stated that there are a number of ultrasound markers

in Down’s syndrome which includes nuchal fold thickness, cardiac

abnormalities, duodenal atresia, femur length & pyelectasis [9].

The signs and symptoms of Down’s syndrome are characterised

by neotenization of brain and bodies. Management strategies

such as early childhood intervention, screening from common

problems, medical treatment when indicated, a conductive family

environment and vocational training can improve the overall

development of children with Down’s syndrome [10].

Conclusion

Genetics have always have played a major role in physical

and mental being of an individual. Downs patients being mentally

and medically weak, best care needs to be taken with adequate

precautions.

Read more Lupine

Publishers Blogger Articles please click on: https://lupinepublishers.blogspot.com/

Read more Dentistry Open Access Journal Articles please click on: https://lupine-dentistry-oral-health-care.blogspot.com/

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Post Endodontic Pain Reduction...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Post Endodontic Pain Reduction... : Lupine Publishers | Journal of Otolaryngology Research Impact Fac...