Lupine Publishers | Dental and Oral Health Journals

Abstract

Cardiac diseases require that there is the meticulous maintenance of

oral hygiene to avoid bacteremia, which has been associated

with rheumatic heart disease and bacterial endocarditis. The aim was to

establish the utilisation of oral health care and oral health

practices of the caregiver about the oral hygiene and caries experience

of children aged 3-12 years suffering from heart disease and

were attending three pediatric cardiology clinics in Nairobi, Kenya. The

study was descriptive and cross-sectional. It involved a study

sample of children suffering from different types of cardiac conditions

and attending the Pediatric cardiac clinics in three public

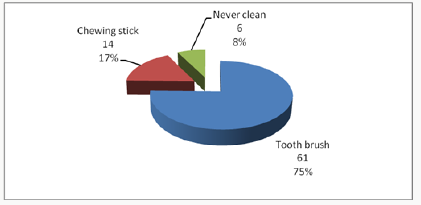

institutions in Nairobi Kenya. The instruments the caregivers used to

brush the children’s teeth were the toothbrush 61(75%);

chewing stick 14(17%) and 6 (8%) never cleaned their teeth. Children who

used a chewing stick had a lower dmft of 1.40±2.98

compared to a dmft of 3.22±3.59 among children who used the toothbrush,

with Mann Whitney U, Z p=0.024 (p≤0.05).The children

who brushed their teeth had a lower mean plaque score of 1.68±0.58

compared those who did not clean with a mean plaque of

2.28±0.40 with a Mann Whitney U, Z=-2.611, p=0.009(p≤0.05). It was noted

that the children who had visited a dentist had a higher

caries experience with a dmft of 4.18±4.13 and DMFT of 1.16±1.92.

However, the children who had never sought treatment at

a dental facility had lower dmft of 1.89±2.88; and DMFT of 0.36±1, and

the differences were statistically significant with Mann

Whitney U, Z p=0.008(p≤0.05). The plaque scores and caries experience

were high in children whose caregivers had low aggregate

utilisation of the oral health care facilities. However, those who had a

low aggregate of oral hygiene practices had slightly higher

plaque scores and caries experience.

Keywords: Cardiac Disease; Children; Utilisation; Oral Health Services; Caregivers

Introduction

Populations with chronic medical illness or other disabilities

had the most unmet needs for oral health services [1], with poor

oral hygiene and increased caries experience than the general

population. For a child from a low-income family with heart

disease, this means an added economic burden in an already tricky

situation [2], as heart diseases necessitate regular dental check-ups

and maintenance of meticulous oral hygiene. This concern has even

been highlighted with new proposals on changes in the guidelines

relating to prophylaxis against infective endocarditis [3,4]. The oral

conditions may have a considerable impact on the general health

status and quality of life of otherwise healthy children, but their

effects on those children with acute and chronic illness can be more

dangerous [5]. Children with cardiac defects and diseases are at

increased risk or even life-threatening complications [6]. Hence the

need for preventive dental health care geared to reducing the risks

associated with management of the oral conditions under general

anaesthesia. Also, the prolonged bleeding from warfarin medication

often taken By the children [7-10]. Poor oral hygiene may give rise

to a frequent bacteraemia under normal physiological conditions,

and this can lead to a permanent risk of developing heart disease

[11-14]. Two common oral diseases, namely periodontal and

dental caries, though preventable, are still more prevalent in Kenya

[15,16]. The children with heart disease have the disadvantage

that their caregivers are preoccupied with the with the primary

medical condition the cardiac disease, resulting in the neglect of

other facets of the child’s total health [17]. The Kenya National Oral

Health policy document has already indicated that the dmft value

for Kenyan 5-year old children as at 2002 was 1.5±2.2, while 43%

of 6-8-year-old children had caries [15], underscoring the fact that

caries is still very rampant amongst the child population in Kenya.

The study was descriptive and cross-sectional where all the

patients aged 3 to 12 years and their caregivers attending paediatric

cardiology clinics over a three month period at Kenyatta National

Hospital (KNH), Gertrude’s Garden Children’s Hospital (GGCH) and

Mater Hospital. A Purposive sampling had been used to select the

study hospitals. Based on Kliegman. study, the study population

sample was determined as 79 cases. However, 81 patients were

recruited in the study. A semi-structured questionnaire was used

to collect information on the socio-demographic characteristics

of the children and the parent/guardian habits on oral health

practices and utilization of oral health services. As children waited

to consult the cardiologist clinical examinations done to record the

oral health status. The examination was conducted using sterilized

instruments and under natural daylight, with the participants

seated on a chair facing the window. Great care was taken during

periodontal probing for gingivitis, to avoid initiating bleeding that

could lead to septicaemia as the children were not on prophylactic

antibiotics. The results were recorded on predesigned individual

questionnaire sheets, and a record of dental caries and plaque was

done. The dental caries was then recorded as dmft for the primary

dentition and DMFT in the permanent [18,19], and the dental

plaque was marked based on the Loe and Silness plaque score

index [20]. Before commencement of the study, the examiner was

calibrated by an experienced paediatric dentist on the collection

of data relating to dental caries, and dental plaque Cohen’s kappa

index score of 0.87 and 0.85 (n=10) was obtained for dental caries

and plaque score respectively. The questionnaire was pre-tested

before use. A duplicate clinical examination was also performed

by the examiner to determine intra-examiner consistency, with

results of Cohen’s kappa index score of 0.91 and 0.86 (n=12) being

obtained for dental caries and plaque score respectively.

Data analysis

The data collected was cleaned, coded and analyzed using

SPSS version 17-computer software from SPSS Inc. IL. The results

obtained were compared and tested using Kruskal Wallis Chi-square

and Mann Whitney U statistical tests, with statistical significance

pegged at 95% confidence interval.

Results

The 81 children in the study, 44 (54.3%) were males and 37

(45.7%) females. Their ages ranged between 3-12 years with a

mean age of 8.16 years (± 2.81 SD), and the 6-9-year-olds accounted

for the most substantial proportion of 33 (40.7%) compared to

the 3-5 year-olds who formed 16(19.8%). The differences in ages

and gender were not statistically significant Chi χ2 =1.287, two

df, p=0.525(p≤0.05). A total of 37(46%) children were from rural

areas, 28(34%) were from Nairobi, and 16(20%) were from other

urban centres other than Nairobi. The distribution of the children

according to the type of heart disease, rheumatic (RHD) accounted

for 36(44.5%) while infective endocarditis (IE) affected 4(4.9%).

The duration since diagnosis of the cardiopathy ranged from less

than one year to 12 years. Nearly half of the children, 40 (49%)

had been diagnosed with the disease for a duration of between

1 to 5 years, while those who had been diagnosed more than five

years and those less than one year accounted for 30% and 21%

respectively. The caregivers’ oral health care practices that included

how the child’s teeth were brushed; the frequency of brushing; and

whether tooth brushing was supervised showed that 75(93%)

children cleaned their teeth and 6(7%) children did not clean their

teeth. Of the group that cleaned their teeth, 33(44%) did it twice a

day, 29(39%) once a day while 16% once in a while/occasionally.

About supervision, 62 (83%) reported cleaning their teeth without

supervision while 13 were assisted by the caregivers. Inquiry on the

ways the child’s teeth were cleaned, 75% (61) of the children used

toothbrush and the rest of the results were as shown in Figure 1.

The children who used toothpaste were 59 (79%) while 16 (21%)

never use any toothpaste.

Considering the utilisation of oral health care services by

children with heart diseases; fifty-nine (72.8%), children had never

visited a dentist or utilised oral health services. Among the 22

(27.2%) children who had been to a dentist, the dental procedure

during the last appointment included extraction 10 (12.3%). Also

cleaning/prophylaxis (1(1.2%)), consultation ; check-up 9(11.1%)

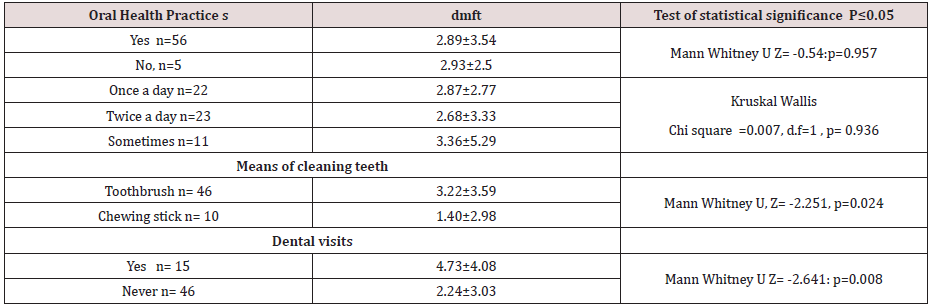

and fillings 2(2.5%).Caregiver’s oral healthcare practices and the

dental caries experience about the children five children who never

cleaned their teeth had a higher dmft of 2.93±2.50 compared to a

lower dmft of 2.89 ±3.54 among the 56 children who cleaned their

teeth, and the differences were insignificant with p=0.957(p≤0.05).

The differences in the frequency of tooth cleaning, the eleven

children who cleaned their teeth once in a while had a higher dmft

of 3.36±5.29 and the 23 children who cleaned twice a day had lower

dmft of 2.68±2.77, but.difference was not statistically significant

with p=0.936(p≤0.05). The children who used a chewing stick had

a lower dmft of 1.40±2.98 compared to a dmft of 3.22±3.59 among

the 46 children who used the toothbrush, with the difference was

not statistically significant, p=0.024(p≤0.05). The children who

had visited the dentist apparently had a higher caries experience

with dmft of 4.18±4.13 and DMFT of 1.16±1.92 when related to the

children who had never visited a dentist, who had lower dmft of

1.89±2.88; and DMFT of 0.36±1. These differences in the results

were statistically significant, p=0.008(p≤0.05). The rest of the

results are as shown in Table 1. When the caregivers were classified

into two groups based on the responses to the oral healthcare

practices as being favourable or unfavourable practices,53 (86%)

caregivers fell in the unfavourable oral healthcare practices. Fiftythree

children whose caregivers displayed unfavourable practices

had a higher dmft of 3.62±3.54 compared to dmft of 2.74±2.85

among the eight children whose caregivers displayed favourable

oral healthcare practices. The difference was statistically significant

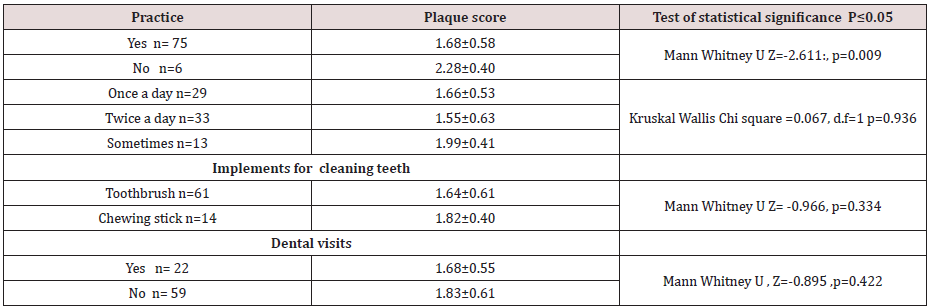

with Mann Whitney U, Z= -1.297, p=0.197(p≤0.05). The mean

plaque score was significantly lower among the 75 children

who reported to cleaning their teeth with mean plaque scores of

1.68±0.58, compared to a higher mean PS of 2.28±0.40 among the

six children who never cleaned their teeth with p=0.009(p≤0.05).

Those children who used the toothbrush had lower mean plaque

scores of 1.64±0.61. The children who cleaned more than twice

a day had the lowest mean plaque score of 1.55±0.63; and those

who cleaned their teeth occasionally had the highest mean plaque

scores of 1.99±0.41, though these differences were not statistically

significant with χ2 =0.067, 1df, p =0.936 (p≤0.05), Table 2. The

mean plaque scores among the 22 (27%) children who had been to a

dentist was mean PS of 1.68±0.55 compared to higher plaque score

of 1.83±0.61 among the 59 (73%) children who had never been to

a dentist Table 2. However, the difference was not significant, with

p=0.422 (p≤0.05)

Discussion

Despite the majority of the respondents, 75(93%), with the

majority reporting that their children cleaned their teeth, only

33(44%) of these children cleaned their teeth at least twice a

day, 62(83%), of them, cleaning their teeth without supervision

by the caregivers. Seven children had never visited a dentist to have teeth cleaned teeth cleaned. Also, some children had

occasional cleaning of their teeth, and this puts the children the

risk of developing early childhood caries, gingivitis, and poor oral

health. The poor oral health may which may give rise to frequent

transient bacteremia during mastication or tooth brushing. Other

studies among children with heart diseases have reported that 55

% of the children brushed their teeth twice a day [21,22] and that

46.1% of the children brushed three times a day. Owino et al [26]

reported that 67.5% of the 12-year-old children in a peri-urban

area brushed their teeth. Franco et, al [25] in their study considered

as disappointing the percentage of children with congenital heart

disease who had never visited a dentist, a reflection of other

results obtained in studies by Silva et al [23], Saunders et al.[18],

and Fonseca et al [5]. In this study, the very high percentage of the

children examined had never seen a dentist, with only 22(27.2%)

of the children have been to a dentist before the stu dy. Moreover,

even though, most of the treatment, which had been offered during

their visit to the dentist, was extraction, just as reported in a study,

Ober et al [24]. The finding is alarming since the American Heart

Association recommends that children with heart disease should

visit a dentist for the institution of preventive measures.

The lower frequency of dental visits in this study compared to

other studies in developed countries could be because of the reasons

that include the fact that; most of the caregivers are ignorant on the

importance of preventive dental care among the children with heart

disease. Most of the patients examined were of lower socioeconomic

status, therefore, could not afford the treatment. Also; the dental

facilities in Kenya are limited, inaccessible and most of them lack

skilled dental personnel who are well trained to offer treatment

to children with special needs. The use of other tooth cleaning

devices like the chewing stick was illustrated in this study. Majority

of the children who were using this device were mostly from rural

areas where other tooth cleaning aids may not be available. The

outstanding fact was that the children examined were from different

residential backgrounds. The patients who used the chewing stick

in this study had significantly lower dental caries experience than

those who used the toothbrush. The low caries experience in the

children who used the chewing stick may be because they could

not afford the snacks between meals. The low could probably be

explained by the fact most of the children who used the chewing

stick were from rural areas where the dental caries experience was

shown to be lower compared to urban centres possibly because of

the difference in the diet. Also, some studies have demonstrated the

cariostatic and bacteriostatic properties of some specific species of

trees, which are used as chewing sticks. It is also possible that a few

children who started to use the brush late in life after severe early

childhood caries had been established could have skewed the high

caries experience illustrated among the children who were using

the brush.

The caregivers’ aggregate oral healthcare practices did not

significantly influence the dental caries experience among the

children in the present study. The lack of differences in the gadgets

for cleaning the teeth may be due to the small sample size where there

was a loss of statistical power. Fifty-three (65; 4%) children whose

caregivers were classified as portraying “unfavorable practices”

had higher caries experience with mean dmft of 3.62±3.54 (n=53)

compared to 2.74±2.85 (n=8) among the children whose caregivers

reported “unfavorable practices” on oral care. The children who had

been to a dentist had a higher dmft than those children who had

never been to a dentist. This finding illustrates that children visit a

dentist when dental disease dental caries has already occurred and

that the majority of the treatment offered was curative to relieve

the symptoms, with little or no emphasis on preventive oral care.

The lack of focus on preventive oral care was further illustrated

by the high proportion of active, untreated caries component of

dmft compared to filled or extracted teeth. Despite the fact that

caregivers’ aggregate oral health care practices had no significant

relationship with the oral hygiene of the children as noted earlier,

thirteen children whose caregivers reported “favourable practices”

had lower plaque scores of 1.69 ±0.54. However, the plaque scores

of sixty-eight children whose caregiver’s had reported favourable

practices had a mean plaque score of 1.73±0.59 slightly higher.The

children who cleaned their teeth had significantly lower plaque

scores compared to those children who never cleaned teeth. The

children whose teeth were never cleaned were at high risk of

developing sub acute bacterial endocarditis when compared to

the children who cleaned teeth regularly. As during the tooth

brushing process, there is the mechanical removal plaque thus

reducing the possibility of increased bacterial colonization of the

plaque and reducing chances of bacteraemia during mastication.

It was noted the that toothbrushes were more effective in control

of plaque compared to the use of chewing sticks, though there

was no significant difference between the two groups. The results

of these study showed that children who had been to a dentist

displayed better oral hygiene than those children who had never

been to a dentist, though there was no statistical difference. The

difference perhaps indicates that the dentist visited previously

could have offered oral hygiene instructions on good tooth brushing

techniques. In addition to that, the caregivers’ aggregate oral

healthcare practices did not significantly influence dental caries

experience among the children. Those children whose caregivers

were classified as portraying “unfavorable practices “on oral care,

had higher caries experience with mean dmft of 3.62±3.54 (n=53)

compared to 2.74±2.85 (n=8).

The children who had been to a dentist had higher dmft than

those children who had never been to a dentist. The finding may be

rationalised that children who visited the dentist they did so when

dental caries had already occurred. The primary treatment offered

was curative to relieve the symptoms, with little or no emphasis

on preventive oral care. The situation was further illustrated by

the high proportion of active, untreated caries component of dmft

compared to filled or extracted teeth.

Conclusion

The utilization of oral health care and oral health practices of

the caregiver of the children was low, and only apparent used in

case of emergency mainly. The oral hygiene, gingival index and

dental caries experience in the study population was high.

Study limitations

The study was only for three months. Hence children who had

had appointments in the previous clinics were excluded. The small

sample size based in three cardiology clinics may have created a

bias. The clinic was limited to 3-23-year-olds excluding the older

children 13-17 this is the policy on how paediatric age cut off as

defined by the ministry of health.

Acknowledgment

We thank Professor Loice Gathece for contribution in the design

of the study. The Kenyatta National Hospital and the University

of Nairobi Ethics and Research Committee fors approval of the

proposal. Alice Lakati who helped in statistical work and Dr. E.

Kagereki and Dr. Kiprop for data entry. The Nurses and the staff at

the Paediatric Cardiac clinics at the KNH, Mater Hospital and the

Gertrudes’ Garden children Hospital for facilitating data collection

during the clinical examinations for the patients. We acknowledge

all the parents and children who participated in the study without

whom the study would not have been a success.

Read more Lupine Publishers Blogger Articles please click on: https://lupinepublishers.blogspot.com/

Read more Lupine Dentistry Journal Blogger Articles Please click on:

| https://lupine-dentistry-oral-health-care.blogspot.com/

Follow on Linkedin :

https://www.linkedin.com/company/lupinepublishers

|

No comments:

Post a Comment