Lupine Publishers | Dentistry Open Access Journals

Abstract

Severe early childhood caries (Severe-ECC) is an aggressive,

infectious and preventable form of dental caries that affects very

young children. The survey purposed to examine any differences in the

severity of poor nutrition in children without decay and

those children with dental decay in the age group between thirty-six and

sixty months. Sampling was purposeful and 196 children

aged between 3 to 5 years for this study. The study was hospital-based

where eighty-one children with severe dental decay who had

attended the Nyanza Provincial General Hospital (NNPGH). Similarly, one

hundred and fifteen children who were caries free were

chosen from amongst the children attending the maternal child health

clinic at NNPGH over a period of three months. Odds Ratio

(OR) and 95% Confidence Interval (CI) were used to estimate the strength

of association between Severe ECC and nutritional status.

The mean dmft for the children with severe Early Childhood Caries (ECC)

was 7.5±19. The prevalence of malnutrition was reported

among both groups of children with severe ECC and without decay as 28

(14.3%) underweight, wasting 5(2.5%), and stunting

9(4.6%). The malnutrition in children with, Severe-ECC was observed as

27(14%) underweight; 10(4.9%) of the children were

wasted, and 5(2.5%) were stunted. However among the children without

caries 26 (13.9%) were underweight while 5 (2.6% were

wasted, and 12 (6.1%) were stunted. Both children those with severe ECC

and those with decay, however, the children who were

likely to be underweight at 1.23 times were those affected with severe

ECC at 1.23 times compared to the children without decay.

Hence other factors may be playing a role in malnutrition of children

aged 3-5year old.

Keywords: Severe-ECC; Nutritional status; Caregivers demographics

Introduction

Early childhood caries (ECC) is defined as the presence of one

or more decayed (non-cavitated or cavitated lesions), those missing

(due to caries), or filled tooth surfaces in any primary tooth in a

child 71 months of age or younger. Severe Early Childhood Caries

reported in children below three years of age as smooth surface

caries1. One or more cavitated, missing teeth due to caries has

been associated with age s 3-5years.The filled smooth surfaces in

primary maxillary anterior teeth or a decayed, missing or filled a

score ≥ 4 for age 3years, a score of ≥ five is associated with 4years

while cavitation, restored tooth and missing due to caries a score of

≥6 is for children in the 5-year-old group. All these scores constitute

Severe – ECC [1].

Disadvantaged groups have been found to be vulnerable to

ECC in both developed and developing countries and even within a

single country disparity by social standing there exist, differences

due to diet, fluoride use, and social empowerment. Disparities in

social empowerment may persist due to lack of access to dental

care and inadequate utilisation of dental care even when available

[2]. Untreated caries and associated infections can cause pain,

discomfort, reduced intake of foods because eating is painful

[3]. Pain may also because the child refuses the caregiver from

maintaining good oral hygiene for the child. There is a paucity of

literature on the prevalence of Severe -ECC in Kenya. However, a

study conducted in nursery school children in Nairobi on the on

dental caries and dietary patterns reported a prevalence of 63.5%

among 3-5 years old [4]. A survey conducted in Kiambaa division in

Kiambu County, a peri-urban population, reported ECC prevalence

in 3 - 5-year-olds of 59.5% [5]. Several studies on nutritional status

and dental caries have reported variable results. A retrospective

survey on the body mass index was done in the United States of

America, and it involved two hundred and ninety-three children

aged two to five years with Severe - ECC receiving dental treatment

under general anaesthesia. In the study, the weight groups were

defined by being assigned the CDC body mass index about on age

and gender of the children. Results showed that the distribution

of subjects by percentiles and the children who were underweight

were 11%; of the study sample. However the children whose weight

was normal weight 67%; at risk of overweight 9%; overweight

11%. This study concluded that significantly, more children in the

sample were underweight than in the reference population [6].

However comparative research on the nutritional status and dental

caries among a large sample of four and five-year-old South African

children found no significant association between the prevalence of

caries and stunting or wasting. However, a relationship was found

between decayed, missing and filled surfaces and wasting [7]. This

study, therefore, aimed to compare the nutritional status of children

aged 3 – 5 years with Severe-ECC and the nutritional status of those

aged 3-5 years without caries.

Severe ECC is also associated with oral Microbiota, and in

particular anaerobic bacteria of the species Scardovia Wigggsiae

and others have been found in abundance in severe ECC lesions [8]

Materials and Methods

One hundred and ninety-six children aged between 3 to 5 years

were recruited for this study. Purposive sampling was done to select

Eighty-one children with Severe - ECC was chosen from amongst

the patients who had sought dental treatment at the dental clinic

at the Nyanza Provincial General Hospital (NNPGH). However,

115 children who were caries free were selected from amongst

the children attending the maternal child health clinic at NNPGH

over a period of three months. Inclusion criteria were: the child

was 3 – 5 years of age, was medically healthy, and the parent or

caregiver was willing to consent. A semi-structured questionnaire

was administered to the caregiver in a face to face interview, and

information was collected on the socio-demographic background

of the children. There gathered data included education level, age,

gender, and the caregiver’s, occupation, and area of residence of

the caregivers. The Intraoral examination was carried using dental

mirrors and a Michigan O dental probe under natural light as the

child sat on an ordinary chair facing the light. Severe ECC was

defined as decayed, missing or filled a score of ≥ 4 (age 3), ≥ 5 (age

4), ≥ 6 (age 5). Before dental caries diagnosis, each tooth was dried

using a piece of sterile gauze. WHO 1997 caries diagnosis criteria

were used, and dental caries was diagnosed when there was a

clinically detectable loss of tooth substance and when such damage

had been treated with fillings or extraction [9]. Anthropometric

measurements were determined to assess the nutritional status of

the children and height of the children were obtained by measuring

the child standing when standing erect and barefoot, using a

measured with a standard height board to the nearest 0.5cm. Weight

for age was measured using a Salter scale to the nearest 0.1kg. Each

parameter of height and weight had three measurements taken,

and an average of each was then recorded. The Cut-offs +2 standard

deviations (SD) were used to identify children at significant risk for

either delayed (<-2SD) or excessive (>+2SD) growth. The indicators

were weight-for-age (WAZ), height-for-weight (HAZ), weight-forheight

(WHZ) based on the World Health Organisation(WHO) 2005

recommended reference standard [10]. The collected data collected

were coded, cleaned and analysed using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS

Inc, Chicago Illinois, USA) for Windows and Microsoft Office Excel

2007. Nutritional data was analyzed using Epi-Nutri program of

Epi-Info version 3.5.1. Descriptive statistics such as proportions

were used to summarize categorical variables while measures of

central tendency such as mean, standard deviations and ranges

were used to summarise continuous variables. The strength of

association was established between categorical values using a

Pearson’s Chi-square tests. Odds Ratio (OR) and 95% Confidence

Interval (CI) were used to estimate the strength of association

between independent variables and the dependent variable. The

multivariate analysis was done using binary logistic regression at

a statistical significance set at p≤0.05. The relevant research and

ethics approving institutions approved the study.

Results

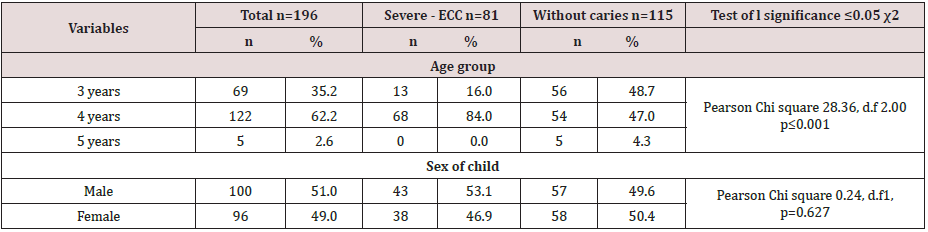

A total of 196 children aged 3-5 years were recruited into the

study, eighty-one children with S - ECC (41.3%) and 115(58.7%)

without caries. The study group had a mean age of 4.1 + 0.6years,

and it ranged from 3- 5 years with a high proportion of the children

(62.2%) aged four years. There was a statistically significant

difference in age distribution among children with Severe ECC and

children without caries (χ2=28.36, d.f=2, p<0.001). The majority of

the children with caries were aged four years (84.0%) compared to

those without caries (47.0%).Gender distribution was comparable

with boys slightly more (51.0%) than girls (49.0%).

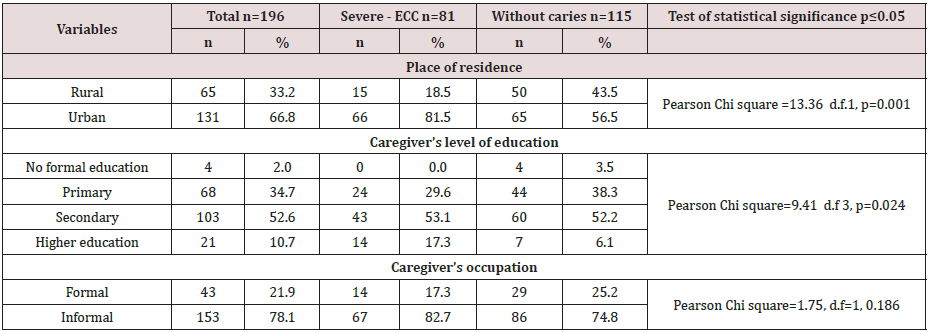

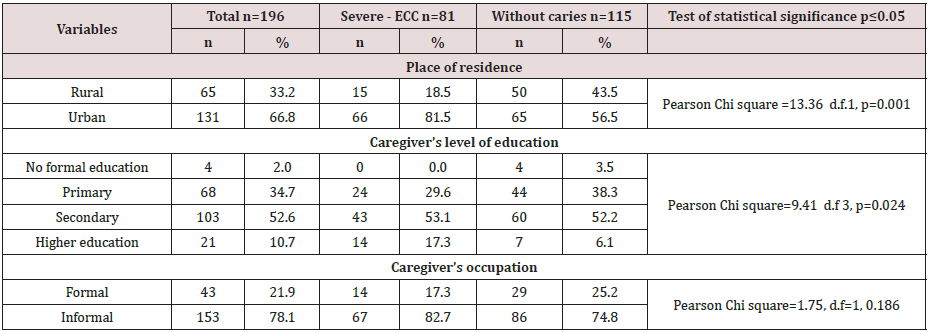

Sixty-five children (33.2%) lived in the rural community, and

131(66.8%) lived in the urban area. The differences in the area

of residence were significant with a Pearson chi square=13.36,

df=1, p≤0.001) for the children with severe ECC and those children

without decay. It was noted that sixty-six (81.5%) out of 81

children with Severe ECC lived in an urban setting when compared

to children who were caries- free who had 65 (56.5%) out of 115

children who were caries free. Some sixty-eight caregivers had

had primary school education of whom 24 (29.6% had severe ECC

while 44 (38.3%)) were caries free. However, 103 caregivers had secondary school education of whom 43 (53.1% had severe-ECC

and60 (52.2%), while 21 (10.7%) their caregivers had tertiary

education and 14 (17.3%) and seven 6.1% were caries free. Also,

children whose caregivers had a primary level of education had

the highest prevalence of severe-ECC followed by those whose

caregivers had secondary education. The differences in the severecares

prevalence were significant with a Pearson Chi-square =9.41

d.f 3, p≤0.024 Table 1 & 2.

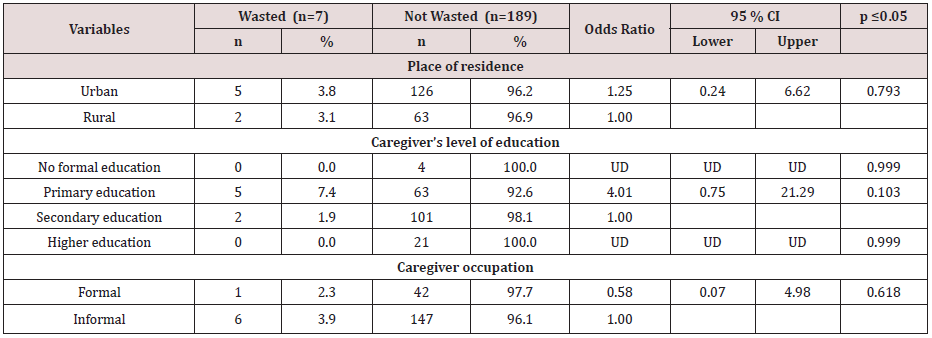

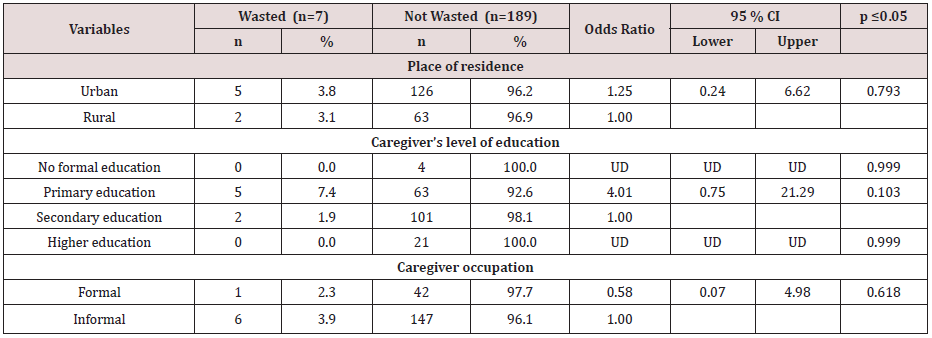

Table 2: Level of education, demographics for the caregivers, place of residence, level of education, and occupation.

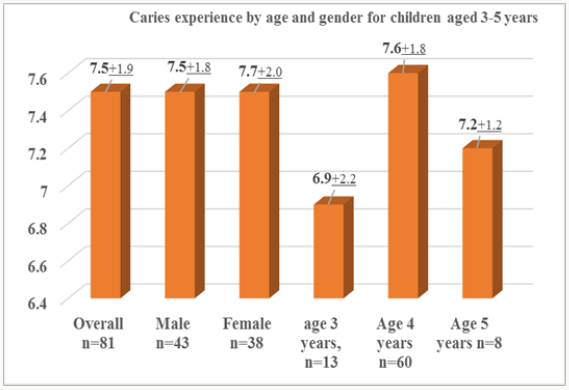

The mean dmft of 7; 5±1.9 d was observed among children with

Severe – ECC, and it ranged from 5 to 12 scores. Scores. However,

the mean dmft for the males was 7.5±1.8 and for females (7.5±2.0),

which was statistically insignificant difference found between the

two groups (t=0.15, p=0.88). The mean dmft score for children

aged three years was 6.9 ± 2.2, four years was 7.6 ± 1.9, and for

five-year-olds was 7.2 ±1.2 and all the dmft ranged from 5-12. The

dmft progressively increased with age and peaked at age four years.

There were no statistically significant differences found between

the age groups (t=1.59, p=0.248). Figure 1.

Overall the decayed component of the dmft contributed 92.3%.

The missing and filled component of the dmft contributed 7.4%

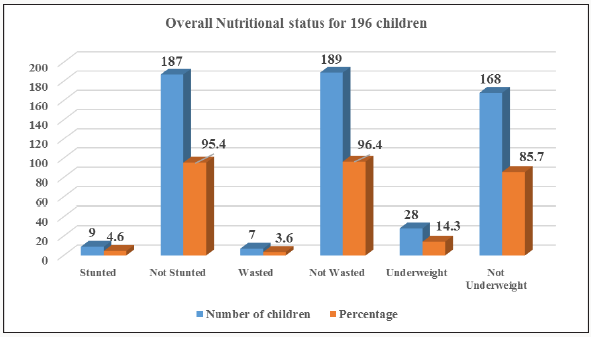

and 0.3% respectively. The overall prevalence of underweight for

acute malnutrition, stunting, and wasting for chronic malnutrition

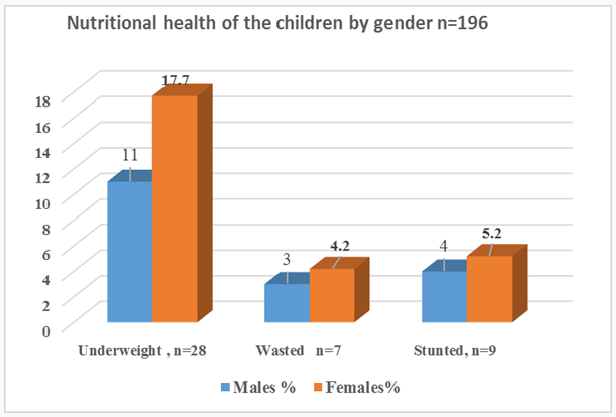

was 14.3%, 4.6%, and 3.6% respectively. There were more females

17(17.7%), 4 (4.2%), and 5 (5.2%) who were underweight,

wasted and stunted respectively when compared to males, but

this difference was not statistically significant Pearson Chi-square

respectively for underweight, stunted and wasted were 1.80,df=1,

p=0.180 ; 0.19,d. f=1, p=0.660 and 0.16, d.f=1, p=0.686 Figures 2

& 3.

Table 3: Underweight among children with caregivers place residence, level of education, and occupation.

When the caregiver’s residence, level of education, and occupation

were considered the children who lived in the rural areas had

higher prevalences of were underweight 10(15.4%), when

compared to the children in the urban areas 18(13.7%) resided in

urban areas. Sixty-eight children had caregivers whose education

was of a primary level, and 11(16.2%) of the children were

underweight while 57 (83.8%) had normal weight for age. Children

whose parents had a secondary education were 103 of whom 14

(13.6% were underweight, and 89 (86,4%) had normal weight for

an age while caregivers who had higher education were eighteen

of whom 3(14.3%) were underweight, and 15( 85.7%) had normal

weight. There were more underweight children 24(15,7) out of 153

when weight for age was examined about the caregivers who were

informally employed, However, the differences in the children who

were underweight with the caregiver’s various demographics were

not significant Table 3.

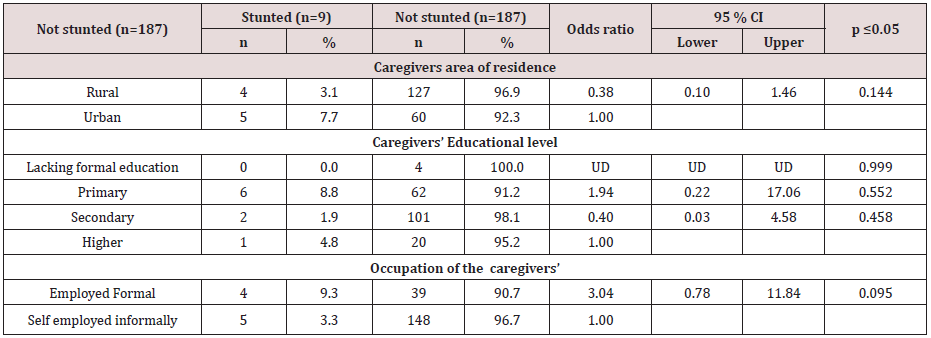

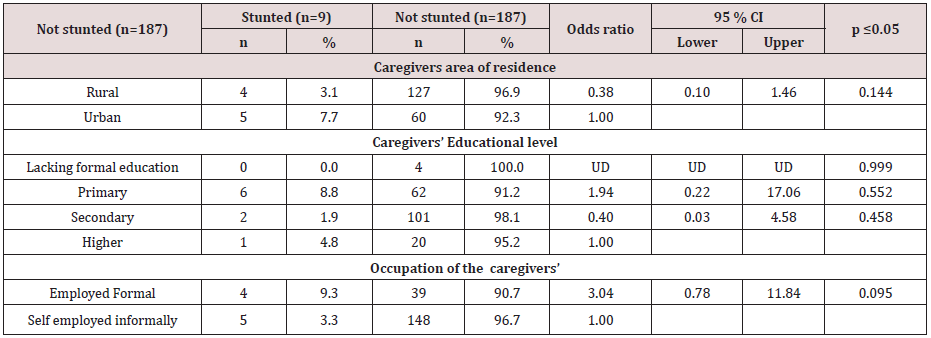

According to the educational level, the children who were

stunted and whose parents had a primary education were four

(9.3%)), secondary 6(8.8%), and higher education were 5(7.7%).

The caregivers who had formally employed were from the urban

area while those who were informally employed and had primary

school education were from the rural areas Table 4. There were

statistically insignificant differences in the caregiver’s place of

residence, the level of education, and occupation among children

who stunted and those who were not stunted.

Table 4: Stunting among children about caregivers place of residence, level of education, and occupation.

For the children who were wasted five 7.4% of the caregivers

lived in the Urban area and had a primary level of education; also

6(3.9%) of the caregivers had informal employment, and 2(3.1%)

resided in rural areas Table 5. There statistically insignificant

differences in the caregiver’s place of residence, the level of

education, and occupation among children who wasted and those

who were not wasted.

Table 5: Wasting among children about caregivers place of residence, level of education, and occupation.

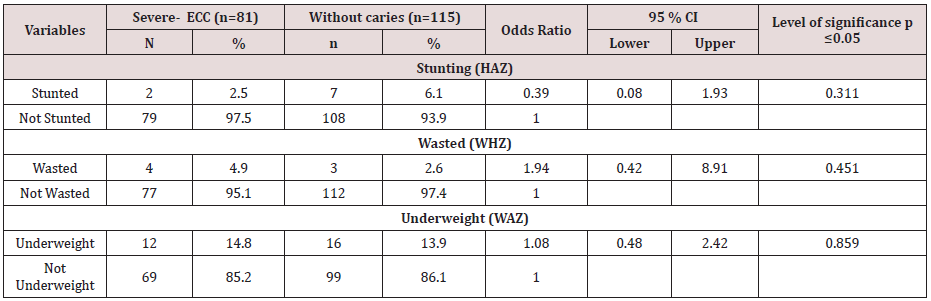

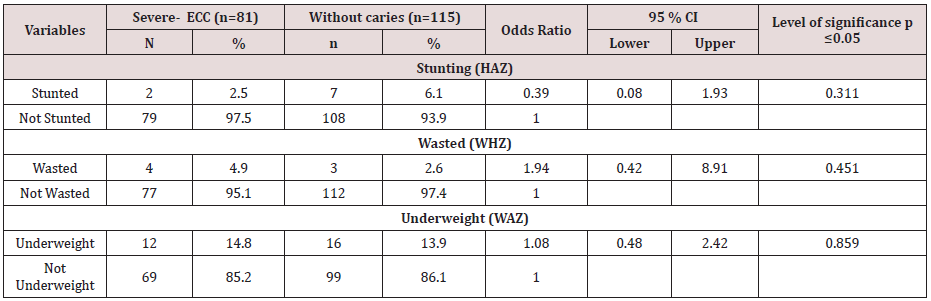

There was a slightly higher prevalence of underweight

14’8% for the children suffering from severe ECC compared with

children without decay 13.9%. Although there were differences

in the nutritional status of children with severe- ECC and children

without caries the differences were insignificant for stunting with

p=0.311; also underweight was insignificant with p=0.859 while wasting had p=0.451). A child identified with Severe- ECC at risk

1.08 more times likely to become underweight when compared to

a child who did not have decay odds ratio lower and upper limits of

0.48 and 2.4 at 95% CL Table 6.

Table 6: Comparison of the nutritional status of children with Severe ECC and children without caries.

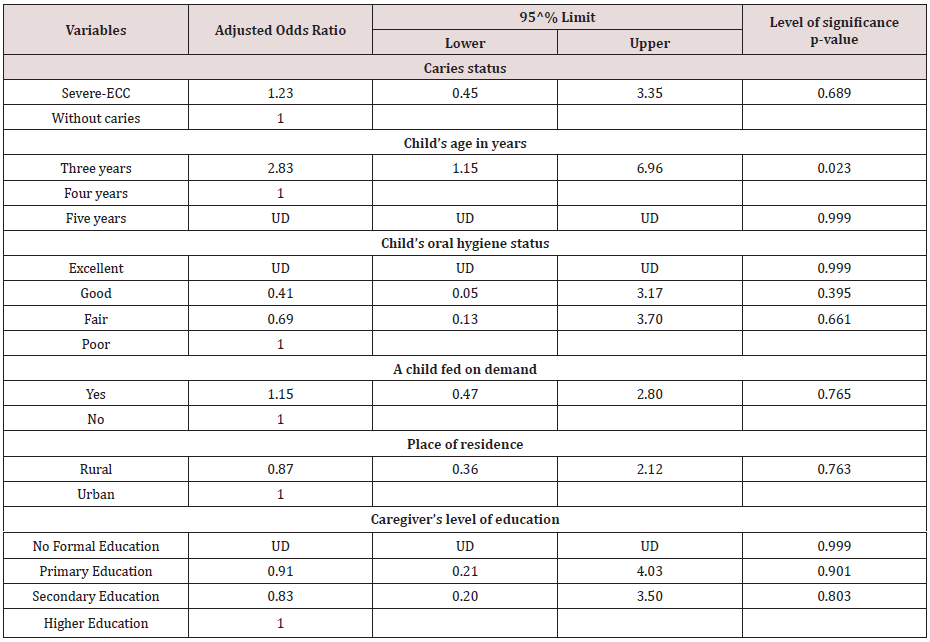

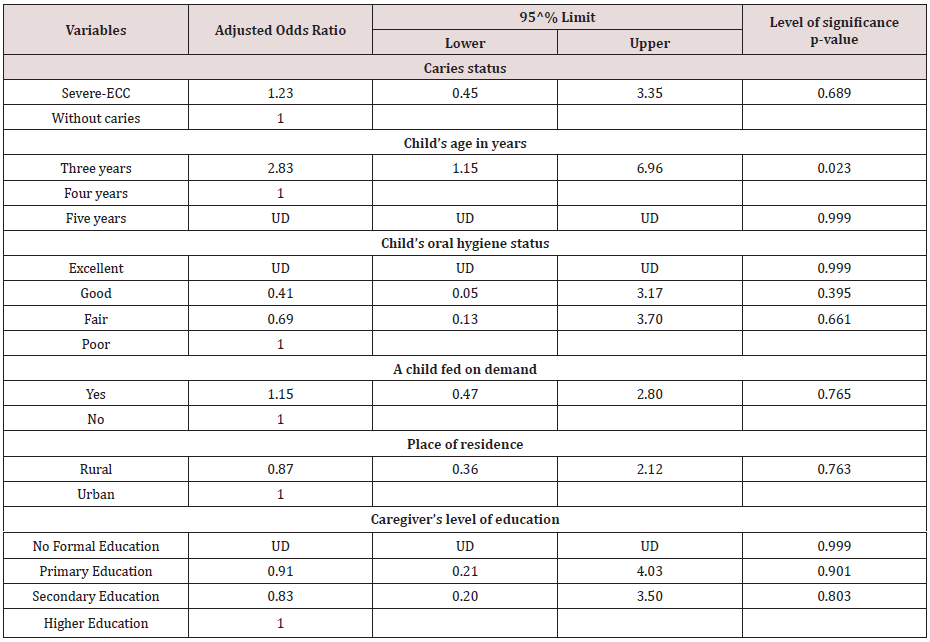

Multivariate analysis was done to determine the relationship

between underweight and Severe- ECC among the participating

children. Five factors associated with underweight and Severe-

ECC at P≤0.05 during bivariate analysis were considered for

multivariable analysis upon fitting the factors using binary logistic

regression. Adjusting for child’s age in years, child’s oral hygiene

status, child feeding on demand, place of residence and caregiver’s

level of education, the occurrence of S-ECC was not significantly

associated with underweight (AOR=1.23; 95% CI: 0.45 – 3.35;

p=0.689). However, a child with S – ECC was 1.23 times more

likely to have low weight for an age when compared to a child

who was caries – free. However adjusting for other factors, age

three years was found to be statistically significantly associated

with underweight with an Adjusted Odds Ratio value =2.83; 95%

CI: 1.15 – 6.96; p=0.023 Table 7. A child aged three years was 2.83

times more likely to be underweight when compared to one aged

four years.

Table 7: Logistic Regression Predicting underweight using caries status, Child’s age in years, Child’s oral hygiene status, Child

feeding on demand, Place of residence and Caregivers level of education.

Discussion

In the current study found that children with severe ECC were

mainly from urban areas in comparison to children who were

caries free. The finding of a high prevalence of severe –ECC in the

urban children is similar to other studies in Kenya and elsewhere

that have shown that children residing in urban areas have a

higher caries experience than their rural counterparts [4,5,11,12].

The mean dmft of children with severe ECC in the present study

was 7.5+1.9 which is comparable to a study carried out among

preschool children of low socioeconomic status in India which

reported a mean dmft of 8.9 [13]. Studies in the USA, and Canada

among preschool children found mean dmft scores of 9.6±3.6 and

10.5 respectively [13-15]. The differences in the mean dmft may be

due to variations in dietary practices among different populations.

Also, decayed component accounted for 92.3% of the dmft, and

this finding was similar to a study in South Africa [14]. Untreated

tooth decay reflects a low utilisation of oral health services or lack

and inaccessibility of preventive and curative dental services to the

caregivers, or if the facilities are available, they are too costly.

Higher caries experience was observed in the children from the

urban areas when compared to their rural counterparts [11]. The

mean dmft of children with severe ECC in the present study was

7.5+1.9. The caries experience for severe-ECC in the present study

is comparable to a study carried out in a low social, economic status

in India among preschooler and reported a mean dmft of 8.9[112].

Studies in the USA, and Canada among preschool children have

reported mean dmft scores of 9.6±3.6 and 10.5 respectively [13,14].

The differences in the dmft could be due to variations in dietary

practices among different populations. The decayed component in

the current study accounted for 92.3% of the dmft, which similar

to other studies elsewhere [14]. Untreated tooth decay reflects a

low availability and accessibility of preventive and curative dental

services.

In this study, there were more females were underweight,

stunted, and wasted when compared to males when referenced

on the WHO reference standard. However, the differences were

insignificant. The WHO child growth standards reference was used

to evaluate nutritional status. The WHO growth reference provides

a scientifically reliable yardstick of children’s growth achieved

under desirable health and nutritional conditions and establishes

the breastfed infant has been used as a reference against whom

other alternative feeding practices are measured to and compare

to regarding growth, health, and development of in children [9].

The children with severe-ECC who were underweight were 4.9%,

stunted 2.5%, and those who were wasted were 14.8%. The presence

of underweight, stunting, and wasting may be associated with the

inability of the children with severe-ECC to chew the available

food and absorb enough nutrients resulting in faltering nutritional

status. In comparison a study carried out in Italy among 2- 6 years

old found that 11% were e underweight, 11.11% overweight and

22.2% to be at risk of overweight [15]. A study in the USA reporting

on the BMI of children with severe ECC noted those who were

underweight as 11.%, overweight 11%, and those who were at risk

of overweight were nine %6. These findings were insignificant may

be due to differences in cultural, dietary practices and the primary

determinants of nutritional status among the different populations.

In Kenya, the primary determinants of nutritional status among

children under five years of age include poverty, hunger, and

drought [16]. The low weight for age observed with urban children

is similar to previous research from other countries where children

with high prevalence with severe-ECC had low weight for age [17].

Children who were malnourished were also noted to have

severe ECC compared to children who were caries free. There are

high levels of malnutrition in Nyanza as reported in the Kenya

Demographic and Health Survey 2008-2009 where 19%, 2%, and

14%of the children under five years were underweight, wasted and

stunted respectively [18]. Considering the caregiver’s demographic

factors children who had low weight for age, wasting and

stunted, resided in rural areas. Also, their caregivers had informal

employment and had a primary level of education.The finding may

be related to the low socioeconomic status and affect access to

health care, food security and hence changing overall nutritional

status [16,17].

The differences in the nutritional status of the children with ECC

and those without ECC was insignificant. South African children

aged between four and five years reported similar findings as what

has been observed in this study. Njoroge et al. reported 60% in a

study population of 338 children aged five years and below[4]. The

most affected dentition were the upper central incisors however

the severity of decay increased with age and the first and the second

deciduous molars had the highest prevalence ranging between 57%

-66%. In this study, the caregivers knew the importance of good

oral hygiene and significance of snacks about caries formation.

However, the infant feeding habits and the weaning practices were

not reported on in this study [19,20].

The South African Study found no relationship between the

prevalence stunting or wasting with dental caries. However,

they reported an association between Wasting with the decayed,

missing and filled tooth surfaces [7]. Children with severe ECC

were 1.23 times more likely to be underweight when compared to children without caries. Severe ECC may affect general health

and development because a toothache associated with caries may

affect food intake and sleep [1]. Poor oral health associated with

pain may interfere with the intake, mastication digestion of food

and nutrients which may lead to decrease in good nutritional health

and reduced quality of life for a child [1].

In summary, the difference in the nutritional status of children

with severe ECC and children without caries and stunting was

insignificant p=0.311, Underweight p=0.859 and wasting p=0.451.

However, children with Severe ECC were 1.23 .times more likely to

be underweight than children without caries.

Read more Lupine Publishers Blogger Articles please click on: https://lupinepublishers.blogspot.com/

Read more Lupine Dentistry Journal Blogger Articles please click on: https://lupine-dentistry-oral-health-care.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment